Grade: A-

For someone who talks and writes about movies more than any other single subject, including physics, which I am studying in a PhD program, I have a lot of major movie blind spots. As I write this, I still haven’t seen some of what people consider the best movies of all time, movies like Lawrence of Arabia, Schindler’s List, or 2001: A Space Odyssey. Last week, however, I did manage to remove one very important entry from that list with The Graduate (1967).

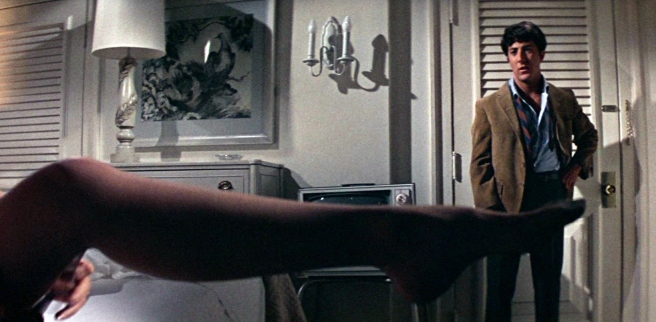

The Graduate, from director Mike Nichols, was released almost fifty years ago now, but compared against its contemporaries, the film seems much newer. The premise, a disturbing love (or lust, perhaps) triangle between a burnt out recent college graduate, the much-older wife of his father’s business partner, and her daughter, seems riskier than normal for the time period. The film begins with Ben (Dustin Hoffman) returning home to Los Angeles after his graduation, jaded and empty, to a massive party in his honor that he didn’t want and in which he clearly doesn’t fit. Ben attempts to escape the party, and the seductive Mrs. Robinson (Anne Bancroft) corrals him into driving her home, where he finds himself in a compromising position. Though not immediately, Ben begins the affair, which proceeds until he falls for Mrs. Robinson’s daughter Elaine (Katharine Ross). From that point Ben becomes solely focused on winning her heart, and to a delusional level after she learns of his affair and leaves for school in Berkeley. The ending that follows is among the best I have ever seen.

The Graduate is considered a comedy, and very much is one, but you wouldn’t guess it at the start. The film opens with Simon and Garfunkel’s The Sound of Silence, which is a great song but certainly not one with a humorous tone, playing over a long shot of Ben exiting an airport, mostly spent stationary on a moving walkway. It’s a potent intro. The humor begins to arise as Ben is forced to meet the partygoers. Each of them has something absurd to say to the graduate that seems simultaneously silly and an accurate example of shallow real-life conversation. The best example is, of course, the famous encounter with Mr. McGuire. That sort of sets the stage for the movie in general. The Graduate is secretly a farce, a subtle slapstick buried under enough reality to be taken partially seriously. And the serious issues that The Graduate tackles are themselves compelling.

Nichols won the Academy Award for best director with The Graduate, and it isn’t surprising when you see the remarkably creative way he uses sound and imagery, long shots and close shots, and distortion of time and reality in story-telling. He builds Ben’s disconnection from the world out of every single word and object. There’s a sequence coincident with the first consummation of the affair in which weeks pass by like rooms that Ben passes through, implying among other things the blurred nature of his life and how little he is doing with it.

Dustin Hoffman’s performance was particularly enjoyable, because it was wholly identifiable and irritating at the same time. He spends the first half of the film unwillingly subservient, and carries just the right amount of confusion, frustration, and reluctance to seem like the kid, thrust into adulthood without a plan, that he is. Whenever he isn’t getting pushed around by Mrs. Robinson, Mr. Robinson, or his parents, Ben does nothing but lie around or sit and stare. In the second half he becomes assertive, but caustically so. I noticed some interesting parallels between Ben and Travis Bickle from Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, but while Bickle is literally alone, Ben is alone in a crowd, remaining aloof because no one seems to care what he has to say or think. It isn’t surprising that he becomes a creep as the story progresses.

An underlying theme of The Graduate is one more timeless than I, in my ignorance, ever realized. Returning from school, Ben is accosted with expectations that he’ll become a responsible grownup, but he has clearly realized the disappointing truth of graduation: life isn’t any different the day after than it was the day before. While I’d like to think I exert better judgment in general than Ben does in this movie, I must admit that I completely understand Ben’s lethargy and why he would be led into some of the rebellious actions he takes. That’s one of the things that makes the movie fit so well for me: I think a lot of people go to school as much to delay the inevitable adulthood as to get an education, and when it finally comes around, it is frequently unwelcome. Is it any wonder that I’m in grad school straight out of my Bachelor program?

I don’t really have any more to say about The Graduate here. I would praise various scenes, including the impeccable ending, but the details are better left to be seen onscreen than ruined by me. I’ve focused in on Ben as the obvious character to follow, but I’m sure there’s a world to be said about Mrs. Robinson that I might pick up on a second viewing. I’ll just conclude here by saying that if you have ever felt like rejecting adulthood and responsibility, this movie is for you, if only as a warning.

tl;dr: The Graduate’s message may be fifty years old, but it is quite possibly more relevant now than ever.